The Hornet's Nest - Part I

I celebrated a birthday earlier this week.

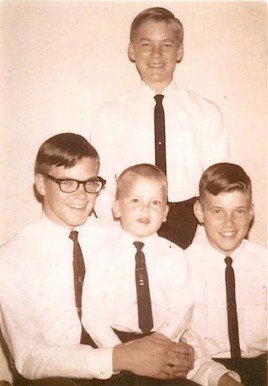

Born at the twilight of the baby boom era, the youngest of four boys. I came of age in a different America. As is always the case with nostalgia, it's all too easy to view the past through a halcion gloss which renders a false picture of what life was really like.

Although there was no Department of Homeland Security and no Patriot Act, there was domestic surveillance on the citizenry, even prior to the FBI's COINTELPRO. But in my time, citing the threat of Communism, the FBI - my government - conducted itself as the arch enemy of the greatest American hero of the 20th Century, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. In the eyes of the federal government, "social justice" was another term for Communism. Now they call it "socialism" - or at least, the fascist footsoldiers do.

As we all know, Dr. King had the audacity - the courage - to boldly demand equality for ALL Americans by ending segregation. He, along with everyone else perceived as threatening the status quo - including the dirty hippies denouncing the wholesale slaughter of the Vietnamese people - were considered nothing short of enemies of the state.

Many a life was intentionally destroyed by the American government. People were forced to make difficult choices. Conscience versus livelihood, family, home, country. It was then that we became - and have since remained - a nation of snitches. Blacklisting. Red-baiting. The House Unamerica Activities Committee. Joe McCarthy. Everyone was motivated by fear. Fear of communism, Big Brother, killing and dying in Vietnam.

Americans put their lives on the front lines of civil disobedience to make this nation more than what it was. Even when Bull Connor's police dogs and water cannons were turned on them, they persisted. When they were jailed, beaten, pistol-whipped, left to injury and death by angry mobs, they persisted. Americans heard the call for justice and action. They - citizens just like you and I - answered that call, and they did so at great personal sacrifice. They had families. Jobs. Pets. Homes. Communities. And they risked it all - everything - to make America a better place.

We have forgotten much and lost our way. These citizen-heroes -- victims of McCarthyism, the campaign against the civil rights and anti-war movements; fighters in a war to better humanity -- they are owed a debt by the rest of us which can never be repaid; but we owe it to them, and ourselves, to do our best to carry on their noble legacies.

My parents were blue collar working folks, smart but - like me - lacking a formal education. Unlike me, they weren't political idealogues, but they did make a conscious effort to be aware of what was going on around them. We subscribed to two newspapers a day. We watched the local and national news together. They neither lionized nor villified Dr. King, and I don't even remember their views on the Vietnam War, although my oldest brother, Robert, served in Vietnam and was fortunate enough to make it home alive, though more scarred than when he joined the U.S. Army.

I have always been a politically-minded person. In elementary school, while other boys were fantasizing about being Evil Knievel or maybe a Beatle, I was trying vain to get my fellow students to walk out and go on strike. They weren't particularly convinced of success and my attempts met with complete and utter failure.

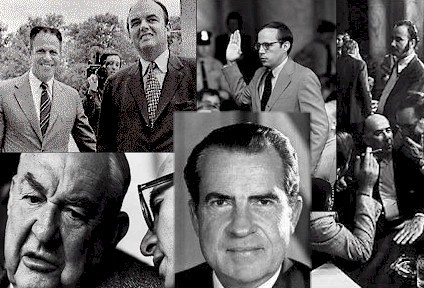

Watergate was a pivotal time in my developing political consciousness. Young people today cannot imagine the permanent stain Richard Nixon left on our country. My friends would come over in the summer while my parents were at work, and they pleaded with me to do something to no avail. I was transfixed on the cast of players testifying on live television. I was eleven years old.

It would be the only time in modern history an American president was held accountable for his official actions. The truth, more evident now than at any time since, is that America never recovered from the fracture caused by Watergate. Democratic leaders would thereafter abdicate their responsibility to assure the public trust was not violated with impunity by the executive branch.

In high school - ninth grade - I was expelled because the back of my hair touched my shirt collar. I called an official in the state arm of Health, Education and Welfare. I still remember his name: Richard Hernandez. I told him what had happened and asked what protections I had, citing Title IX as a possible defense. Mr. Hernandez hemmed and hawed, obviously admiring my chutzpah, but reluctant to immerse himself in the matter and trigger a local firestorm. I could challenge the school system in court, he said, but only if I was willing to stay out of school until my case could be heard, assuming I even had a case.

In the dean's office of my sprawling suburban high school, I asserted Title IX rendered parts of the dress code moot. If girls could have long hair, mine shouldn't pose a problem. Mr. Maines was not a pleasant man - his role had nothing to do with academics and everything to do with being a disciplinarian. He didn't appreciate my challenge. Gary Gilmore was to be executed that morning, and he told me that if I was not more respectful of society's rules, I would ultimately wind up being put to death by the same society which would put a bullet in Gary Gilmore's head.

My mother, a union member who felt the school was overstepping its authority, was not amused at the comparison. After some deliberation, I ended up cutting my hair and going back to school after having had no effect on changing the system. But I never forgot trying. I never forgot that it was important to at least try. A couple of years later, fed up with everything which represented authority, I would quit high school.

Almost thirty years have passed. I married my soulmate, joined the Air Force for a hitch, stayed married. Mrs. Hill and I chose not to have children, preferring peace and quiet and Staffordshire terriers to the monumental responsiblity of parenthood. I worked a number of different jobs, a cog in many a corporate machine, paid my taxes, and fulfilled my civic duty, if minimally. I never abandoned my distrust of authority and cynicism about societal norms. And I never became Gary Gilmore.

Part II to follow.

Born at the twilight of the baby boom era, the youngest of four boys. I came of age in a different America. As is always the case with nostalgia, it's all too easy to view the past through a halcion gloss which renders a false picture of what life was really like.

Although there was no Department of Homeland Security and no Patriot Act, there was domestic surveillance on the citizenry, even prior to the FBI's COINTELPRO. But in my time, citing the threat of Communism, the FBI - my government - conducted itself as the arch enemy of the greatest American hero of the 20th Century, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. In the eyes of the federal government, "social justice" was another term for Communism. Now they call it "socialism" - or at least, the fascist footsoldiers do.

As we all know, Dr. King had the audacity - the courage - to boldly demand equality for ALL Americans by ending segregation. He, along with everyone else perceived as threatening the status quo - including the dirty hippies denouncing the wholesale slaughter of the Vietnamese people - were considered nothing short of enemies of the state.

Many a life was intentionally destroyed by the American government. People were forced to make difficult choices. Conscience versus livelihood, family, home, country. It was then that we became - and have since remained - a nation of snitches. Blacklisting. Red-baiting. The House Unamerica Activities Committee. Joe McCarthy. Everyone was motivated by fear. Fear of communism, Big Brother, killing and dying in Vietnam.

Americans put their lives on the front lines of civil disobedience to make this nation more than what it was. Even when Bull Connor's police dogs and water cannons were turned on them, they persisted. When they were jailed, beaten, pistol-whipped, left to injury and death by angry mobs, they persisted. Americans heard the call for justice and action. They - citizens just like you and I - answered that call, and they did so at great personal sacrifice. They had families. Jobs. Pets. Homes. Communities. And they risked it all - everything - to make America a better place.

We have forgotten much and lost our way. These citizen-heroes -- victims of McCarthyism, the campaign against the civil rights and anti-war movements; fighters in a war to better humanity -- they are owed a debt by the rest of us which can never be repaid; but we owe it to them, and ourselves, to do our best to carry on their noble legacies.

My parents were blue collar working folks, smart but - like me - lacking a formal education. Unlike me, they weren't political idealogues, but they did make a conscious effort to be aware of what was going on around them. We subscribed to two newspapers a day. We watched the local and national news together. They neither lionized nor villified Dr. King, and I don't even remember their views on the Vietnam War, although my oldest brother, Robert, served in Vietnam and was fortunate enough to make it home alive, though more scarred than when he joined the U.S. Army.

I have always been a politically-minded person. In elementary school, while other boys were fantasizing about being Evil Knievel or maybe a Beatle, I was trying vain to get my fellow students to walk out and go on strike. They weren't particularly convinced of success and my attempts met with complete and utter failure.

Watergate was a pivotal time in my developing political consciousness. Young people today cannot imagine the permanent stain Richard Nixon left on our country. My friends would come over in the summer while my parents were at work, and they pleaded with me to do something to no avail. I was transfixed on the cast of players testifying on live television. I was eleven years old.

It would be the only time in modern history an American president was held accountable for his official actions. The truth, more evident now than at any time since, is that America never recovered from the fracture caused by Watergate. Democratic leaders would thereafter abdicate their responsibility to assure the public trust was not violated with impunity by the executive branch.

In high school - ninth grade - I was expelled because the back of my hair touched my shirt collar. I called an official in the state arm of Health, Education and Welfare. I still remember his name: Richard Hernandez. I told him what had happened and asked what protections I had, citing Title IX as a possible defense. Mr. Hernandez hemmed and hawed, obviously admiring my chutzpah, but reluctant to immerse himself in the matter and trigger a local firestorm. I could challenge the school system in court, he said, but only if I was willing to stay out of school until my case could be heard, assuming I even had a case.

In the dean's office of my sprawling suburban high school, I asserted Title IX rendered parts of the dress code moot. If girls could have long hair, mine shouldn't pose a problem. Mr. Maines was not a pleasant man - his role had nothing to do with academics and everything to do with being a disciplinarian. He didn't appreciate my challenge. Gary Gilmore was to be executed that morning, and he told me that if I was not more respectful of society's rules, I would ultimately wind up being put to death by the same society which would put a bullet in Gary Gilmore's head.

My mother, a union member who felt the school was overstepping its authority, was not amused at the comparison. After some deliberation, I ended up cutting my hair and going back to school after having had no effect on changing the system. But I never forgot trying. I never forgot that it was important to at least try. A couple of years later, fed up with everything which represented authority, I would quit high school.

Almost thirty years have passed. I married my soulmate, joined the Air Force for a hitch, stayed married. Mrs. Hill and I chose not to have children, preferring peace and quiet and Staffordshire terriers to the monumental responsiblity of parenthood. I worked a number of different jobs, a cog in many a corporate machine, paid my taxes, and fulfilled my civic duty, if minimally. I never abandoned my distrust of authority and cynicism about societal norms. And I never became Gary Gilmore.

<< Home